When foreign species settle into new territory, the results can be dramatic—and not in a good way. In the Pacific states, a growing list of outsiders is wreaking havoc on everything from redwood forests to coastal waters. Some arrived by accident, while others were the result of human carelessness. Either way, their impact is anything but subtle. These disruptors outcompete natives and leave environmental messes in their wake. Let’s explore the worst ecological party crashers in the West.

Amathia Verticillata (Spaghetti Bryozoan)

With its translucent, noodle-like form, Amathia verticillata often gets mistaken for sea fluff. But this bryozoan forms colonies that clog harbors and foul gear. Its arrival in Puget Sound shows it can survive in varied temperatures, and it isn’t going anywhere soon.

Watersipora Subtorquata (Orange Zooid Bryozoan)

This copper-resistant bryozoan clings to boats and docks like wet carpet. The thick, orange mats it forms outcompete mussels and native reef dwellers. First seen in California in the ’90s, it now thrives as far north as Washington.

Didemnum Vexillum (Marine Vomit Tunicate)

Nicknamed “sea vomit,” it’s more than just gross. Such a Tunicate grows over an inch per day in prime conditions. It also disrupts aquaculture and outpaces control efforts. DNA testing revealed its Asian origin, which overturned earlier assumptions that it was native to the region.

Undaria Pinnatifida (Asian Kelp)

Better known as wakame in sushi rolls, it’s anything but appetizing in the wild. This kelp grows up to 2 centimeters daily and spreads from a single spore. First spotted in California harbors in the early 2000s, it now dominates over 20 coastal zones, outcompeting native kelp forests.

Clavelina Lepadiformis (Light Bulb Tunicate)

Its name comes from its bulbous, translucent shape—but there’s nothing gentle about it. It filters huge volumes of plankton, starving fish nurseries of food and space. Brought in with shellfish stock, it has no natural predators locally and can regenerate from fragments. Hence, even manual removal is nearly futile.

Bugula Neritina (Spiral Tuft Bryozoan)

At first glance, it resembles harmless purple seaweed. Look closer, and you’ll find it stifling shellfish habitats and riding boat hulls to new marinas. Though it produces bryostatin—a compound with cancer research potential—it disrupts oyster farms and thrives in polluted, low-oxygen zones along urban coastlines.

Grateloupia Turuturu (Devil’s Tongue Seaweed)

This fast-growing red algae can double in size in a week and reach six feet in length. It traveled from Japan to every coastal state from Baja to British Columbia. Its resilience includes surviving days out of water, which makes it an all-too-easy hitchhiker on boats and fishing gear.

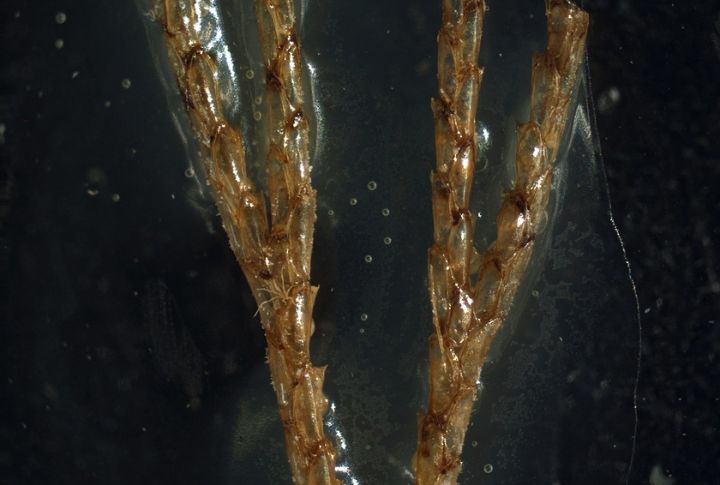

Caprella Mutica (Japanese Skeleton Shrimp)

The wiry amphipod forms dense clusters on ropes and piers, rapidly replacing native shrimp species. Its relentless feeding on larval plankton disrupts early food chains. Many first encountered it in Puget Sound, but it likely slipped in unnoticed on seaweed and oyster shells.

Schizoporella Japonica (Orange Encrusting Bryozoan)

Bright orange and unyielding, this bryozoan blankets rocks and even living barnacles. It was first identified in Washington in 2013, likely introduced through Japanese fishing gear. Its ability to survive out of water for over 36 hours and resist antifouling measures makes it especially hard to contain.

Carcinus Maenas (European Green Crab)

Feasting its way through clam beds, the marine invader eats up to 40 juveniles a day. It showed up in San Francisco Bay in 1989 and has steadily expanded northward. In fact, its adaptability to changing salinity and a lack of predators has led to millions in damage across the shellfish industry.