Humans weren’t always the only ones strolling around on two legs and making tools. Long before smartphones and small talk, other species left their footprints behind—some short, some strange, all extinct. Curious how deep our family tree goes? Let’s meet the long-lost cousins you never knew you had.

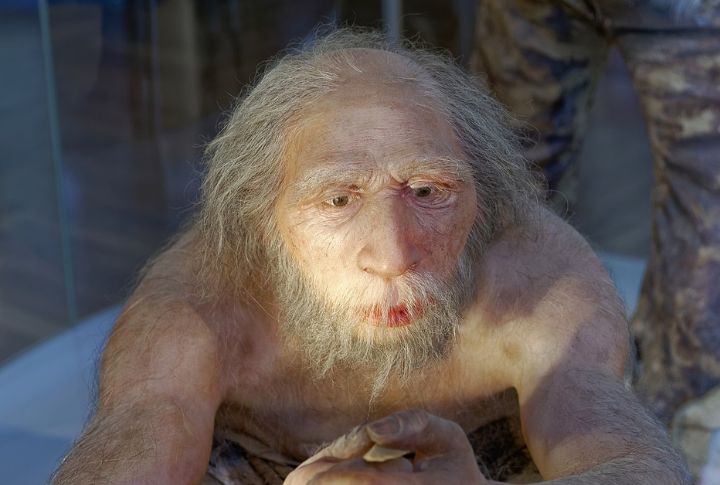

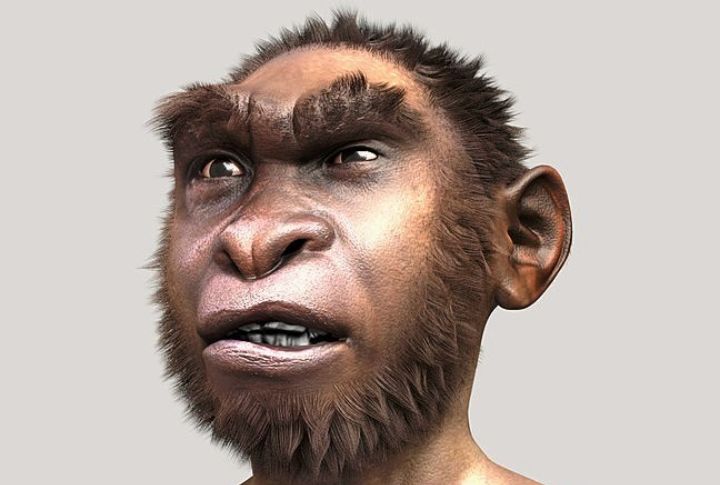

Neanderthals

Built for survival, these Ice Age humans had dense bones, muscular bodies, and wide noses—traits that helped them endure Europe’s frigid climate. Their brains averaged 1,450 cc—larger than yours. Still, their tools remained relatively basic. Interbreeding has also left Neanderthal DNA in about 1% to 2% of modern human populations outside Africa.

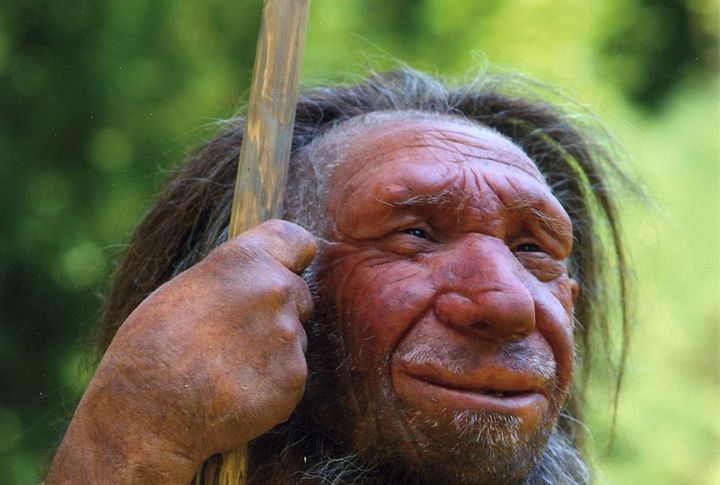

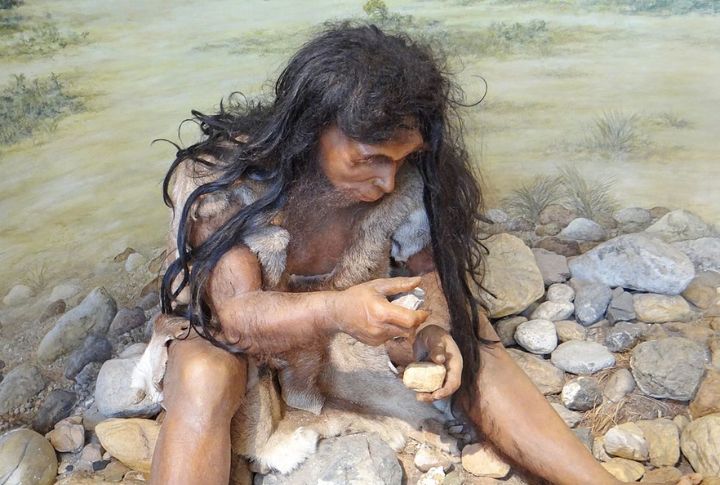

Homo Erectus

Could long-distance travel have begun with them? Likely yes. They left Africa nearly 2 million years ago, reaching Asia and Europe. Brain sizes ranged from 850–1,200 cc, paired with athletic limbs. Mastery of fire and symmetrical hand axes suggests survival wasn’t just luck—it was methodical, mobile, and physical.

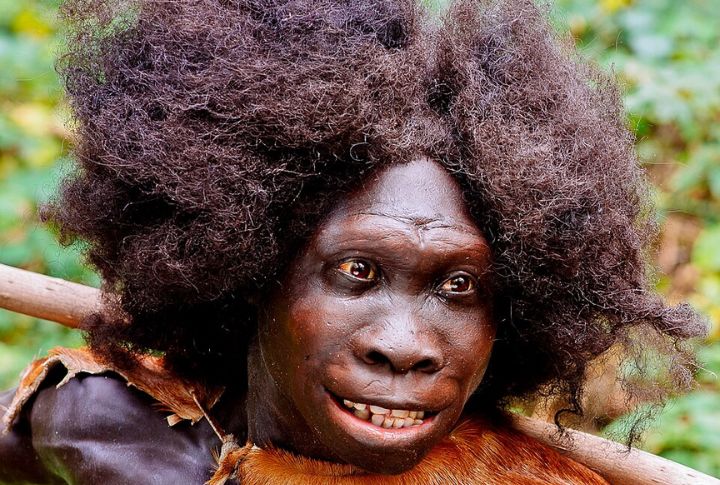

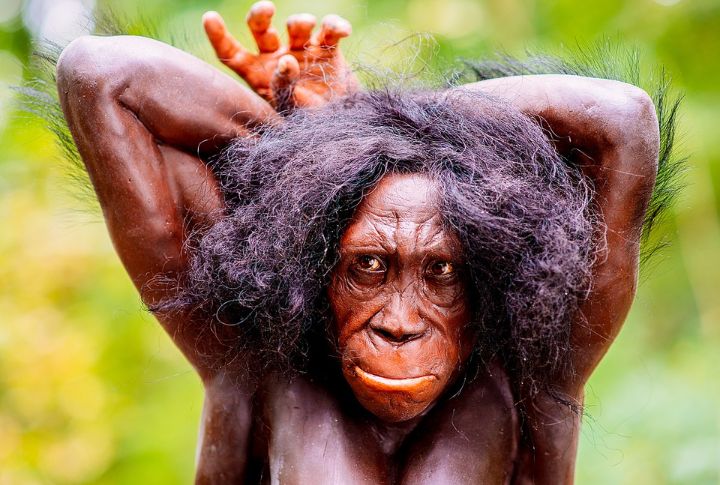

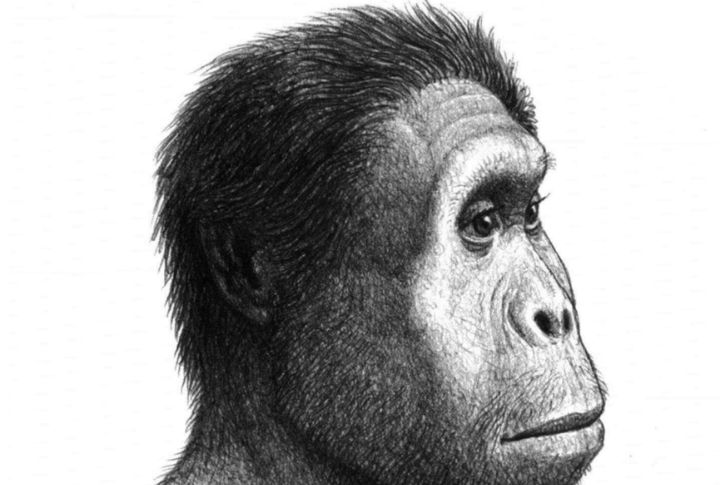

Ardipithecus Ramidus

Fossils over 4.4 million years old, discovered in Ethiopia, revealed a creature adapted to both bipedal walking and life in trees. Their small canine teeth, unlike chimps, point to social behavior changes. At about 4 feet tall, their anatomy challenges traditional assumptions about the earliest upright human relatives.

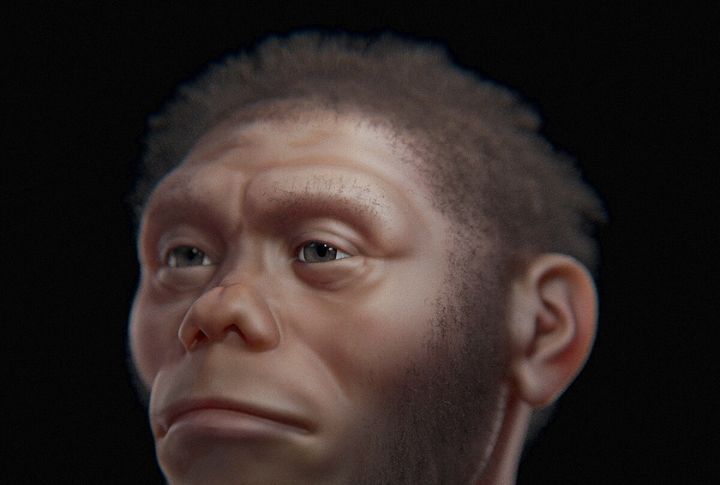

Homo Floresiensis

What lived on Flores Island was a 3.5-foot-tall hominin with a chimp-sized brain. Yet these “hobbits” crafted sharp tools and hunted pygmy elephants. Evolution’s oddities, like island dwarfism, likely explain their tiny frames. They survived until about 50,000 years ago—alongside much taller and better-known Homo sapiens.

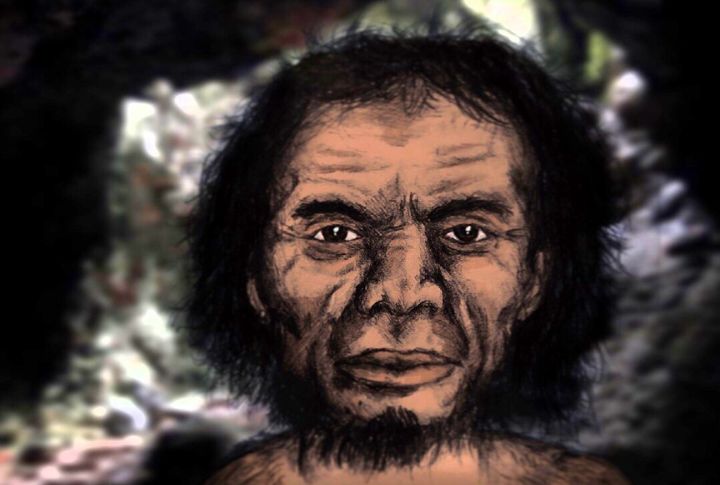

Homo Heidelbergensis

Larger game didn’t stand much chance. These early humans wielded wooden spears to take down prey as big as horses. With brains nearing 1,300 cc, they also built shelters and organized communal hunts. Their descendants may include both Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, depending on where their groups migrated next.

Australopithecus Sediba

Unearthed in 2008 near Johannesburg, their skeletal remains blended traits from both earlier Australopithecines and later Homo species. Their long arms suggest tree climbing, but pelvis and leg structures hint at upright walking. Dated to about 2 million years ago, Sediba may represent a transitional phase in human ancestry.

Homo Luzonensis

Molar teeth discovered in Luzon’s Callao Cave shocked researchers in 2019. These belonged to a small-bodied human species, only three to four feet tall. Their toe and finger bones displayed a mix of ancestral and derived traits. Homo luzonensis lived around 67,000 years ago, adding a surprising new branch to the human family tree and challenging earlier theories about early human migration in Southeast Asia.

Denisovans

Not many fossils exist—just a pinky bone, teeth, and a jaw—but their DNA told the real story. Denisovans contributed up to 5% of the genome in some Melanesian groups. Found in Siberia’s Denisovan Cave, they remain genetically closer to Neanderthals than modern humans, yet entirely distinct in their adaptations.

Homo Rudolfensis

Lake Turkana’s discovery in 1972 sparked an intense debate. Was this a new species, or just a variation within Homo habilis? Larger teeth, a flatter face, and a 750 cc brain suggest something different. Classification still divides paleoanthropologists, but many agree that Rudolfensis walked an important but unclear path in human evolution.

Homo Ergaster

Fire crackled beside their campsites in Africa nearly 1.8 million years ago. Taller and leaner than their predecessors, they likely thrived in open savannahs. A 900 cc brain supported early toolmaking skills. Often regarded as Homo erectus’ African form, Ergaster represents a major shift in body structure and behavior alike.