Embark on a brief journey through human evolution as we encounter iconic figures such as Sahelanthropus tchadensis (“Toumaï”), Ardipithecus kadabba, Orrorin tugenensis, and more. From bipedal locomotion to genetic legacies, each breed offers a glimpse into our ancestral past, shaping the diverse tapestry of humanity.

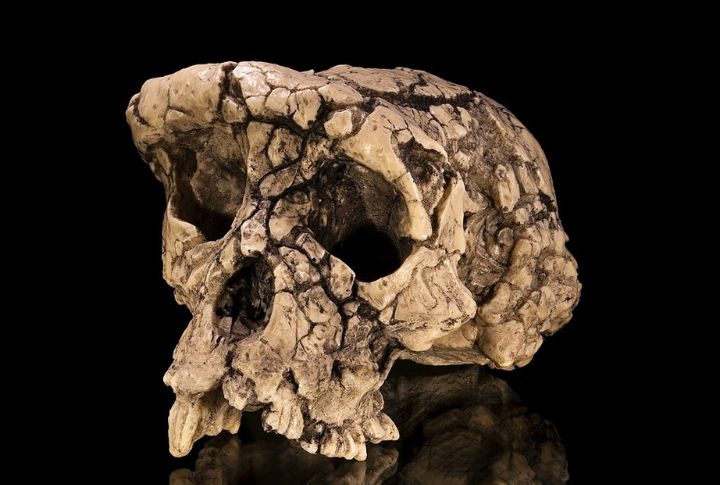

Sahelanthropus Tchadensis (“Toumaï”)

Dating back approximately 7 million years, Sahelanthropus tchadensis is one of the earliest known hominins. Discovered in Chad, Central Africa, in 2001, it has a combination of ape-like and humanity attributes, suggesting it may be a common ancestor to chimpanzees too.

Ardipithecus Kadabba

Ardipithecus kadabba was excavated in the Middle Awash Valley of Ethiopia, roughly 5.8 and 5.2 million. This ancient hominid, Ardipithecus kadabba, exhibited upright locomotion, akin to modern chimpanzees, with a body and brain size reminiscent of the same. Notably, its canines, though akin to later hominins, protruded beyond the tooth row.

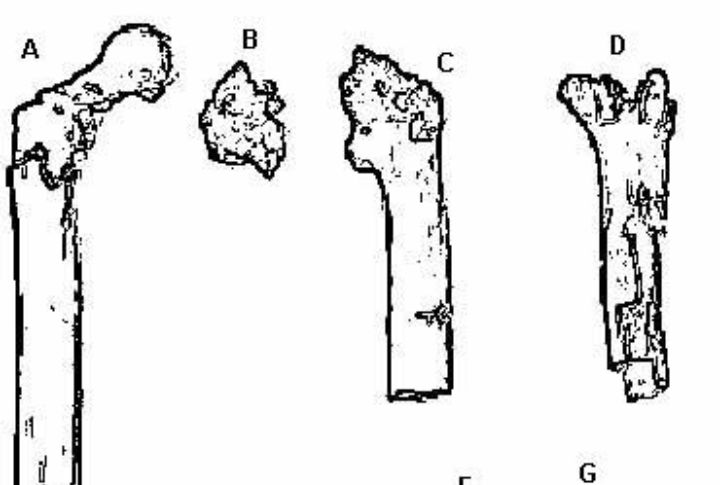

Orrorin Tugenensis

In the past 6 million years, this species has lived in Kenya and was discovered in 2000. Orrorin tugenensis is significant as it provides evidence of bipedalism, or walking on two legs, at an earlier stage of evolution.

Ardi

They originated 4.4 million years ago in Eastern Africa. Ardi’s foot bones exhibit a distinctive large toe and a rigid foot structure. The reconstructed pelvis suggests adaptations for both tree-climbing and two-legged activity. Significantly, Ardi’s canine teeth show minimal variation in size between males and females.

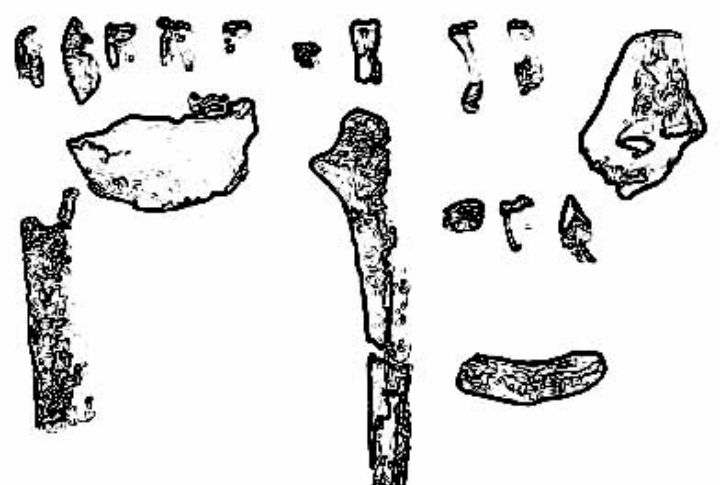

Australopithecus anamensis

Notably, the upper end of the tibia (shin bone) exhibits an expanded area of bone and a mortal-like orientation of the ankle joint. Features such as long forearms and wrist structures suggest adaptations for both tree-climbing and ground-dwelling. Dated to approximately 3.8 to 4.2 million years ago, they were discovered in Northern Kenya.

Denisovans

Inhabiting high altitudes in Tibet, Denisovans passed down a gene aiding modern individuals in acclimatizing to similar elevations. They shared a close genetic kinship with Neanderthals, and their genetic legacy persists; around 5% of the ancestry of Oceania’s inhabitants can be traced back to Denisovans.

Homo Erectus

Distinguished by man-like body proportions, Homo erectus boasted shorter arms and elongated legs relative to their torso, a crucial adaptation for proficient bipedal locomotion. Their fossil record spans over 1.5 million years, making them the longest surviving among our man’s relatives.

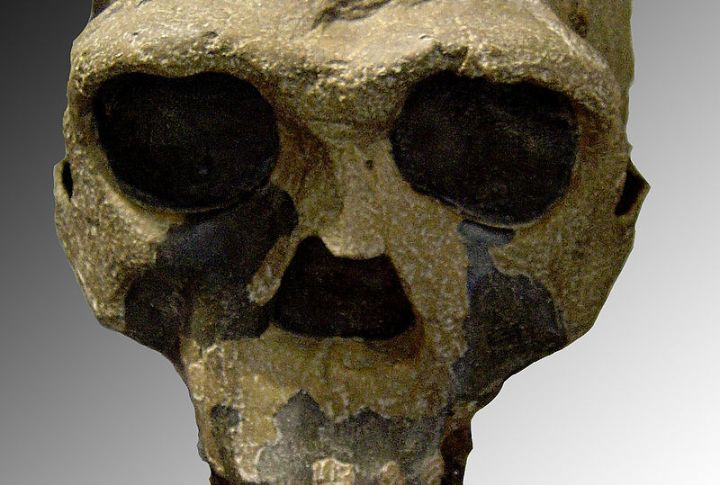

Paranthropus Aethiopicus

The famous “Black Skull,” a 2.5 million-year-old relic, remains emblematic in defining this breed as the inceptive, robust australopithecine. P. aethiopicus is defined by a prominently projecting face, large megadont teeth, and a robust jaw.

Australopithecus Afarensis (“Lucy”)

Australopithecus afarensis, affectionately known as “Lucy,” was unearthed in 1974 in the Hadar region of Ethiopia. Despite her small brain size (approximately 385-550 cm³), Lucy displayed an upright posture and a blend of ape-like and human anatomical traits. Her protruding face and diminutive stature significantly distinguished her within the hominin lineage.

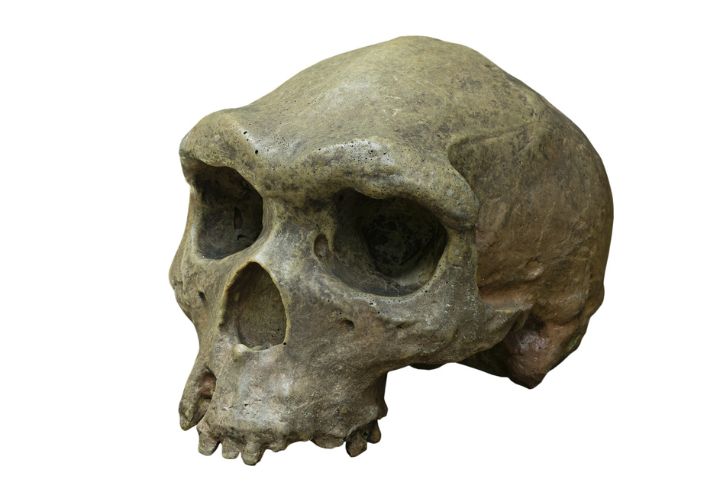

Homo Heidelbergensis

The type specimen, famously known as Mauer 1, consists of a jawbone that provided pivotal evidence for this species. Homo heidelbergensis displayed distinctive traits such as a pronounced brow ridge, an expanded braincase, and a relatively flattened face.

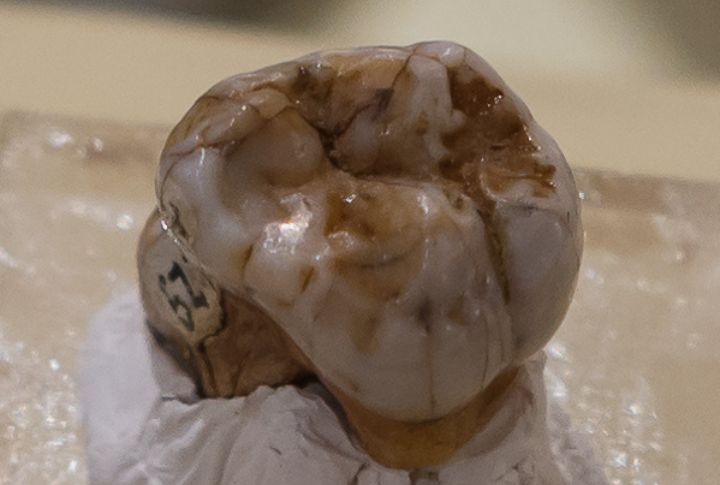

Kenyanthropus platyops

Defined by a flat-faced morphology and relatively diminutive brain size, it thrived roughly 3.5 million years ago. Kenyanthropus exhibited distinct dental characteristics with smaller molars. Its flat facial structure and less pronounced brow ridges have prompted speculation among scientists regarding potential affinities with Homo.

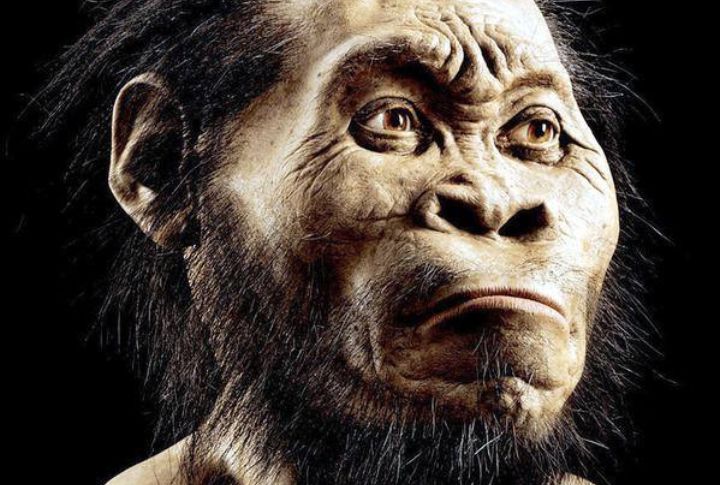

Homo Naledi

These remarkable fossilized remains emerged from the Middle Pleistocene 335,000–236,000 years ago. Homo naledi presents a small cranial capacity, ranging from 465–610 cm³, in stark contrast to modern people. Yet, their person-like body shape, characterized by elongated legs and a relatively diminutive stature, hints at an intriguing blend of ancestral and contemporary traits.

Australopithecus Africanus

The Taung child, a partial skull, was a pivotal find that conclusively demonstrated the presence of early relics in Africa. While exhibiting ape-like attributes such as long arms and a strongly sloping face, Australopithecus africanus was adept at two-legged walking and climbing, showcasing a versatile locomotor repertoire.

Homo Habilis

Homo habilis possesses distinct features that distinguish it from earlier hominins. Remarkably, it exhibits an increased cranial capacity, ranging from 500–900 cm³, indicative of a larger brain than its predecessors. Additionally, its comparatively more minor molar and premolar teeth exhibit closer similarities to those of modern mortals rather than the more primitive Australopithecus.

Homo ergaster

Due to their disproportionately large stature and smaller teeth, Homo ergaster possessed distinctive anatomical traits that set them apart. The original skull, designated as KNM-ER 3733, offers a glimpse into the past, dating back to 1.5–1.9 million years ago.